Early Wins and Challenges in Implementing WIOA Pay-for-Performance to Improve Outcomes for Opportunity Youth

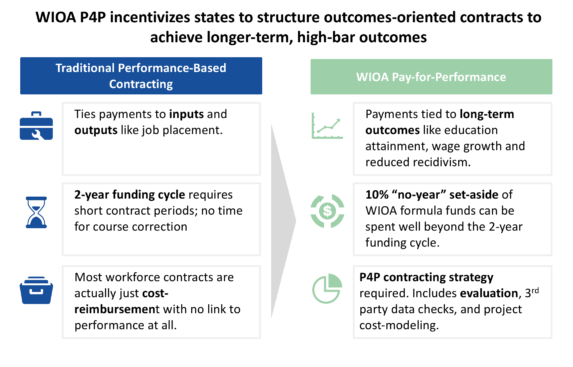

The current public workforce system has left out some of our country’s most vulnerable people. With federal funding spread across 11 agencies and 47 programs, much of the system relies on cost-reimbursement contracts that stifle innovation by 1) prescribing services that prohibit providers from adapting programs to needs and 2) not rewarding providers for improving outcomes. Providers are often paid regardless of results, yielding little incentive to use evidence-based interventions or deploy new technologies. While some programs use something called “performance-based contracting,” much of the time, payments are linked to activities and outputs, like enrollment instead of long-term outcomes like wage growth.

Recognizing the limitations of cost-reimbursement and standard performance-based contracts, Congress and the Department of Labor included important changes in the 2014 Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) to provide an opening to focus on improving outcomes. With a shift towards longer-term outcomes through new performance measures and the authorization of Pay-for-Performance (P4P) contracts, there is a window of opportunity for workforce boards to build on the rich history of performance-based contracting, develop more comprehensive services and deploy resources in increasingly outcomes-driven ways.

In 2016, as our second cohort of Social Innovation Fund sub-recipients and motivated by the new WIOA legislation, Third Sector selected five awardees to receive technical assistance to strengthen youth workforce development programs throughout the United States. Workforce boards in Austin, Boston, Denver, Northern Virginia, and San Diego are currently working with us to explore how the Pay-for-Performance provisions of WIOA can strengthen their programming and develop replicable models to inform and scale outcomes-based contracting across the nation. While the work to develop data sharing agreements, employer partnerships, and P4P contracts is not easy, teams agree that the benefits of improving outcomes for youth while deploying funds more efficiently are well worth the effort.

Project Updates

Pay-for-Performance has provided a rallying point for governments, employers, providers and funders to come together and strategize on how to better serve youth who are not in school and not working, often called “Opportunity Youth,” in these communities. With the Austin Workforce Solutions Capital Area team, we are working to scale the highly successful Youth Employment Partnership program in Austin/Travis County through targeted engagement of employers as end payors who will pay for successful youth outcomes through hiring and retention related fees. By engaging employers as thought partners in developing outcomes-based contracts, we hope to meet the talent needs of employers while improving long-term outcomes for Opportunity Youth in Austin/Travis County.

Boston

In Boston, Third Sector is working with the Mayor’s Office of Workforce Development (OWD) to strengthen their summer youth employment program (SYEP), which provides summer job opportunities to youth, many of whom come from low-income households. Third Sector and Northeastern University’s Dukakis Center are collaborating with OWD to explore opportunities to implement outcomes-based contracting for Boston’s SYEP. We have convened a National Summer Youth Employment Advisory Group to help inform our efforts and ensure that these learnings are disseminated widely, given the popular nature of this program and the variation in quality that exists across programs. Early evaluation results show Boston’s SYEP having significant impact on financial literacy gains and participant’s sense of community involvement, and in some circumstances, involvement with the criminal justice system.

Denver

We are also working with the Denver Office of Economic Development to combine evaluation, and performance-driven service provision to increase educational and employment outcomes for pregnant and parenting youths. We are exploring ways to use existing data systems to track longer-term education and employment outcomes for these populations and blending federal funds with local public funding sources to embed flexible outcomes-based contracting concepts in upcoming youth workforce contracts.

Northern Virginia

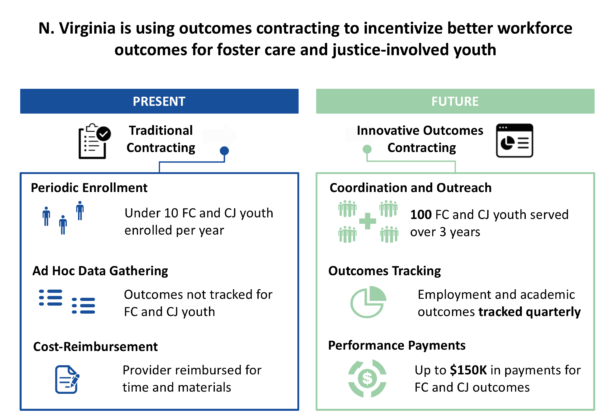

In Northern Virginia, we have partnered with the SkillSource Group to launch a P4P pilot focused on reaching foster care and justice-involved 18-24 year olds in Fairfax, Prince William and Loudoun Counties. To reach a contract, we brought together criminal justice and foster care agencies across the three counties to outline project goals and strategize towards a P4P approach. We are working with service providers to understand service delivery, contracting, the service population and data systems to improve referral pathways and develop a strategy to use existing data systems to measure and evaluate longer-term employment and education outcomes.

San Diego

With the San Diego Workforce Partnership (SDWP), we are exploring the opportunity to use the WIOA P4P provisions to increase the rate of placement and retention in employment or postsecondary education, as well as reduce the rate of recidivism for justice-involved youths. SDWP is interested in shifting its existing contracting process to one that ties payments to performance by using existing data systems to track longer-term education, employment and recidivism outcomes for justice-involved youth in San Diego County, developing an outcomes payment strategy, and designing a contracting and evaluation plan.

Early Wins and Successes

Across this second cohort, themes have emerged about the benefits of engaging P4P to improve workforce outcomes for youth. Categorically, these five jurisdictions have seen learnings and successes emerge around data, outcomes, and evaluation; partnerships and processes; and service provision and the population served. The teams have consistently identified positive advances that will pay dividends in their work beyond this specific effort.

Data, Outcomes, and Evaluation

Success in these areas is measured in a few ways. Many of the sub-recipients noted just getting individuals around the table to talk about data and outcomes was a benefit of this work. Incorporating evaluators into the discussion was new for many localities, and some locations have developed and executed data sharing agreements or the first time. Workforce Board and provider access to justice, tax record, academic, and employment data will be a significant win, allowing for a continuous feedback loop to improve programs and direct funding where it is most needed.

Partnerships and Processes

Forming new partnerships has been another broad success for every sub-recipient. Whether it was brain trusts, working groups, or formal collaboratives, getting folks from inside and outside of government to collaborate in developing an outcomes-based approach has yielded wins across many topics. For example, in Northern Virginia, coordination between workforce, foster care and juvenile justice systems through the P4P contract process has led to a focus on serving youth involved in these systems for the first time. In San Diego, by selecting a shared goal of reducing recidivism, workforce and juvenile justice systems are now working hand in hand.

Service Provision and Population Served

The partnerships formed through this work have enabled in-depth assessments of beneficiary populations, resulting in a deeper understanding of the needs and challenges of typically underserved groups. Through these assessments, many locations were able to reach consensus on a very specific beneficiary population focus and also prioritize where and how to deliver services to achieve the greatest impact. Additionally, for some sites, this work has revealed an opportunity to potentially scale a currently successful intervention that has been limited in its ability to reach the entire priority population.

Challenges and Barriers

Despite the early wins and successes, there are some equally significant challenges and barriers that all the projects have faced and agree are critical to overcome to make WIOA P4P a success. These challenges and barriers fall into the same categories as the early wins and successes: data, outcomes, and evaluation; partnerships and processes; and, service provision and population served. However, there is also a general category that broadly speaks to the reality that P4P in the workforce system context is new, and as a result, there are general knowledge barriers that impact the success of this effort. There are also very specific elements of the P4P authority in WIOA that jurisdictions have identified as challenges and that, without further guidance, could serve as roadblocks to executing P4P contracts for themselves and other jurisdictions.

Data, Outcomes, and Evaluation

There are still sites that face barriers to putting data sharing agreements in place, particularly across government agencies. Most State Longitudinal Data Systems (SLDS) are not set up to serve the needs of local programs or workforce boards, so tracking participants beyond a few quarters after program exit becomes quite difficult. Additionally, most data do not go back further than two years thus limiting the ability to establish historic performance levels, set baseline targets for providers, and ultimately measure long-term performance moving forward.

Partnerships and Processes

Because P4P is new and runs up against current practices and protocols, pushback from some agencies and partners due to heightened risk aversion has slowed progress. Some localities have identified that the lack of a strong government champion has hindered the work.

Employer and provider relationships have also surfaced as a challenge to advancing this work. In many locations, shifts in the provider landscape make developing strong partnerships and establishing common processes difficult.

Implementing WIOA P4P Authority

When WIOA became law in July 2014, it ushered in a new era for federal workforce policy since it updated many elements of the system for the first time in over 15 years. Pay-for-Performance was defined in the law, and has further been elaborated on in final regulations, but defining and authorizing are different from implementing and executing. As a result, all of the localities have identified implementation and execution challenges associated with the WIOA P4P authority that include definitional and application challenges, funding level challenges, and other specific elements of the statutory P4P authority included in the law.

Definition and Application

All five jurisdictions have noted that one challenge to this effort is a lack of understanding within the workforce system of the difference between performance-based contracting and P4P. Though the system has used performance-based approaches, those historically have focused on inputs and outputs, such as enrollment and job placement, versus the targeted focus of the WIOA authority on long-term, high-bar outcomes, such as wage growth over time or reduced recidivism. As a result, the structural elements of a P4P contract are not commonplace in the workforce system and there were not examples of the application of the approach for workforce agencies and boards to call on as they attempt to implement the new P4P authority and execute contracts.

Federal Funding

In addition to this definitional challenge, another basic concern with executing P4P is the uncertainty of federal funding levels year-to-year. Specifically, decreased allocations recently have already required difficult choices to be made about what WIOA programs to fund. Targeting funding for P4P contracts is another strategic decision that workforce entities will now have to consider when allocating limited federal workforce resources. That process will only be made harder if federal funding levels continue to fluctuate or diminish.

‘No Year’ Funding

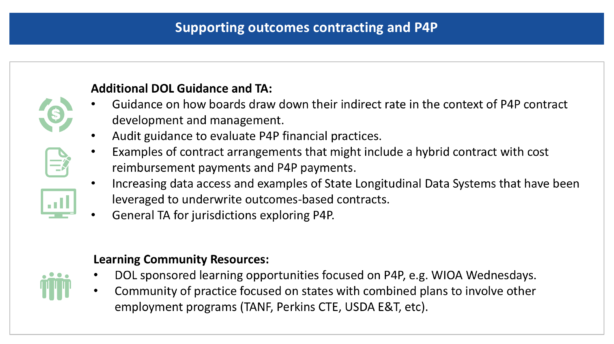

The WIOA P4P authority includes a ‘no-year’ provision for funding allocated to P4P contracts. Specifically, WIOA dollars used for P4P contract strategies “shall remain available until expended.” This notion of being able to ‘set aside’ funding for future expenditure based on an evaluation and the achievement of specific outcomes is unique. It runs up against federal and state budget rules and, to date, DOL has not released guidance or provided technical assistance to help jurisdictions navigate this important element of P4P.

Indirect Cost Rate

Within the context of the P4P percentage set aside of local funds, it is unclear if workforce entities can draw down funds at their indirect cost rate for administrative expenses related to developing a P4P contract. Specifically, it would be a barrier if localities could not draw down these funds regardless of whether the P4P contract is ultimately issued or whether outcome targets are achieved. Without some clarity about the use of the funds and the implications of the indirect cost rate, jurisdictions may be hesitant to implement the authority for fear of using limited dollars or concern for misappropriating them in situations where efforts to execute a P4P contract do not succeed.

Ways to Address the Challenges and Sustain the Early Wins

These are areas where additional guidance would support the workforce system in effectively executing the changes made in WIOA, specifically in using P4P.

These five pilot projects demonstrate the flexibility and diversity that exists within the parameters of WIOA P4P. We believe that these examples can serve as models for other workforce boards across the country, as well as uncover ways that state and national leadership can better support P4P efforts. Increased access to data, including individual tax and wage records, and ensuring that state level policies allow local areas to fully take advantage of the P4P provisions are essential to encouraging continued exploration of P4P. Outreach and collaboration with accounting professionals in state and local government will also ensure that the innovative solutions developed through P4P are supported by financial practices and systems.

Pilot projects will be wrapping up between now and the end of the year, so stay tuned for project summaries and tools based on the successes and challenges we uncover throughout the projects. If you would like to keep up with the progress of these projects, as well as learn about future opportunities to explore P4P in your own community, please contact Celeste Richie at crichie@thirdsectorcap.org.

About the Social Innovation Fund

The Corporation for National and Community Service is the federal agency for volunteering, service, and civic engagement. The agency engages millions of Americans in citizen service through its AmeriCorps, Senior Corps, and Volunteer Generation Fund programs, and leads the nation’s volunteering and service efforts. For more information, visit www.NationalService.gov.

Co-Authored by Celeste Richie, Director, Third Sector Capital Partners and Nicole Truhe, Government Affairs Director, America Forward