Economic Mobility in Practice: How A Focus on Outcomes Changes Everything

Meet a Young Woman we call Rose. Rose is a representative composite of the 4.6 million Americans between 16 and 24 who don’t have full-time employment and are not in school. Like many of her peers, Rose has been juggling several part-time minimum-wage jobs while also serving as the primary caregiver of Samuel, her 2—year-old son. Rose knows that she needs to find a better job - ideally one that leads to a career with benefits and a living wage so that she can adequately care for Samuel. Her old foster care case manager recommends she visit the TANF office (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) in her town. Rose is hesitant. Visiting the office during business hours will mean foregoing work wages and make it harder to cover groceries and bills. Rose is also suspicious of the government institutions she knows: an underfunded school, foster-care bureaucracy, and heavy-handed police. When Rose decides to give it a shot, she sits with Samuel in a waiting room for hours until a case worker hands her a stack of forms to fill out. She is told to come back for an interview in a week because she didn’t bring all of the correct documentation. With a reinforced sense of rejection, Rose knows there is little chance she’ll make it to that follow-up appointment.

The Challenge: A Disjointed System With Multiple Barriers

The legislators who write and the civil servants who administer America’s social safety do not intend for programs to fail the people who need it the most -- yet this is what’s happening for Rose and many others. Between complex administrative procedures, strict eligibility requirements, and a web of services and programs that work in silos rather than in coordination, the U.S. public support system consistently fails to meet Rose and others like her where they are. The obstacles Rose face are symptoms of a system that inadvertently prioritizes services over outcomes and paperwork over people.

A Focus on Economic Mobility: A Way to Rethink the Story

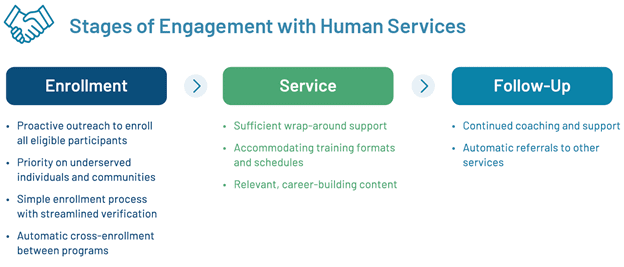

A system that is focused on economic mobility outcomes ensures easy and equitable enrollment in workforce and training programs, effective and relevant service while people are enrolled, and effective follow-up support. Had Rose’s foster care case manager operated in a system that focused on economic mobility, he would have worked more closely with Rose before she aged out at 18 to help her connect with and enroll in other support services that could have provided the necessary education, workforce training, and wrap-around supports (childcare, transportation, etc.) to get on a track to earning a living wage with a long-term career trajectory. If the TANF caseworker had been operating in a system that focused on economic mobility, he would have taken the time to get to know Rose at her first visit and to make sure she was quickly connected to relevant services, including a coach or other mentor to help her navigate the bureaucratic complexity of future training and work requirements.

The Definition: What is a “System Focused On Economic Mobility Outcomes”?

The behaviors and practices of case managers and other frontline staff are governed by the underlying government structure that determines how they do their work. Without addressing this “behind-the-scenes” government structure, it’s unlikely that changes in knowledge, behaviors, and practices will last over time. This government structure, or “system,” includes six levers. When any one of these levers is adjusted in support of economic mobility, that adjustment can spur the kind of change that is necessary to generate impact and last over time. How each of these levers factor into the enrollment, service, and follow-up stages of engagement will determine the success of each stage.

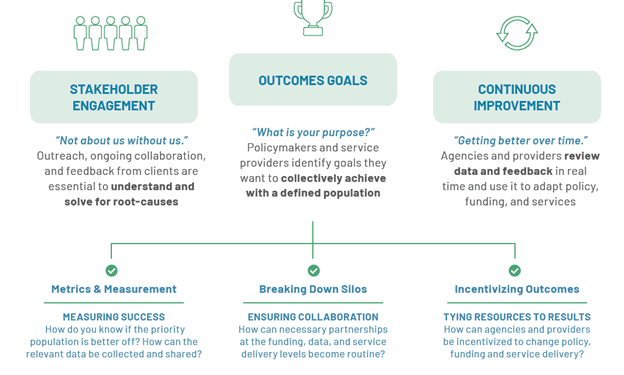

The Process: Six Steps to Transform the System to be Outcomes Focused

To change government levers and structures in support of economic mobility outcomes, agencies have adopted an outcomes-focused approach to systems change. The outcomes-focused approach involves six actions steps that collectively enable agencies to reorient their government levers in support of economic mobility outcomes. The six action steps include goal setting, stakeholder engagement, metrics and measurement, breaking down silos, incentivizing solutions, and continuous improvement.

Economic Mobility in Practice: Four Examples

The examples in the Economic Mobility in Practice Brief include four distinct case studies of states that have adopted the outcomes-focused approach with Third Sector’s help. All of the states looked to improve economic mobility for disadvantaged youth ages 16-24. Youth, especially underserved and marginalized groups, represent a critically important demographic in economic mobility efforts given the lifelong and often multigenerational impacts that programs can have. The four cases in the Brief come from Georgia, Virginia, Massachusetts and Louisiana and involve reorienting one or more of the government levers as part of working through the system change action steps. The cases also focus on different stages of program engagement.

In DeKalb County Georgia, The Georgia Division of Family and Children (DFCS) worked with Third Sector to ensure that young parents transitioning out of foster care at age 18 experience a smooth and effective enrollment with the Office of Family Independence to continue participating in meaningful training and workforce development opportunities.

In Northern Virginia, the local workforce board worked with Third Sector to transform how data, contracts with providers, and service enrollment were use to better engage and support youth that had been involved in the foster care or justice systems. Through this work, the workforce board became the the first workforce entity in the nation to take advantage of the WIOA Pay for Performance provision by establishing bonus payments for service providers to improve longer-term job placement and retention outcomes for “hard to reach” populations.

In Massachusetts, the Department of Transitional Assistance (DTA) worked with Third Sector to break the cycle of poverty where 45% of the young parents they served had themselves grown up in poor families. After setting education and longer-term two-generational economic mobility goals, DTA applied these when engaging and contracting with non-profit service providers thereby giving providers the support and freedom they need to “do whatever it takes” to help young parents thrive.

In New Orleans, Louisiana, the New Orleans Business Alliance (NOLABA) wanted to do more to help “opportunity youth” who were disconnected from work and education achieve economic mobility, and worked with Third Sector to develop an outcomes-focused coaching program that would tie a certain portion of provider payments to longer term economic mobility outcomes. The program was designed as a public-private partnership since youth would be referred to the program while engaging in workforce training services provided by the city’s workforce board.